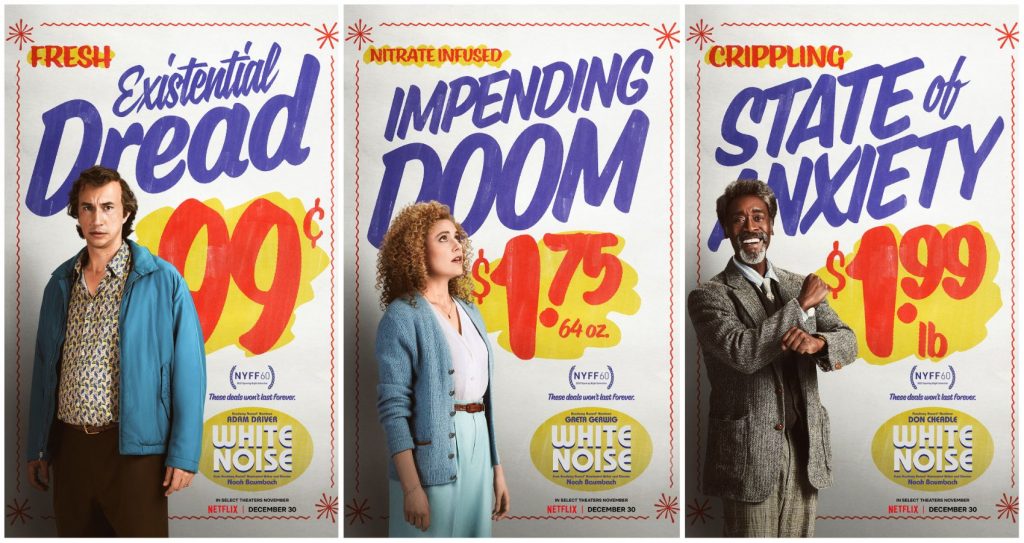

Adam Driver trades Annette for Babette.

Adapted from Don DeLillo’s novel, White Noise is the latest film by Noah Baumbach (Frances Ha, Marriage Story) for Netflix (on December 30th). In preparation for this film, I read White Noise via my trusty Library app so this review will relate the two. The story surrounds the Gladney family in 1985 America- pre, mid, and post an airborne toxic event. Jack Gladney, the family patriarch and professor of Hitler studies at the College-on-the-Hill, is the protagonist in both versions of the story. The perspective shifts from book-to-film. The book is told from Jack’s perspective- a scattered consciousness, attuned to the waves and minutia of his aimless suburban, consumer existence. The film is much more sweeping and epic than the novel, lacking Jack Gladney’s frightened and insecure observations. Jack’s insecurities are a big part of the novel, here they are pushed to the side as subtext. Upfront and center is Jack’s fear of death. Death, and the fear of it, is the film’s biggest theme to pervade the story and characters across the runtime.

It is a big undertaking for any director to attempt an adaptation of White Noise. My thoughts going in were that Noah Baumbach is a trustworthy director to do the text justice. It’s his first time adapting another artist’s work into a feature and he does an admirable job. It was a strange choice to give this such a grand scope with a Spielbergian tone as nothing in the novel (except for the toxic event) really calls for an epic scale. The largeness feels like a minor misstep in the translation from text-to-screen. This would be a bigger issue if not for the fact that Baumbach seemingly puts every single dollar onto the screen and it’s fun to imagine such an indie guy using the keys to the kingdom to adapt such an enigmatic piece of art. The novel puts you in the mind of a deeply insecure man in intimate ways; the film condenses this context into a bigger part of a family unit. In the novel, Babette and Jack are just as simpatico as they are disconnected. In the film, the impact of their disconnect doesn’t land as hard when it’s brought into focus. Jack finds comfort in his stereotypical perceptions of the people in his life. If a person or event throws a wrench in the consistent flow of expectations, the threat of death sits on Jack’s shoulders. In the time of COVID, the existential message of White Noise is clearer. Our convoluted systems and the reliance on the comforts of consumer culture hang on the weak thread of things simply continuing.

Baumbach’s adaptation is comfortable interpreting the book through a Spielbergian lens but it is still smarter than a simple disaster movie. The Netflix trailer makes the film out to be an action/disaster movie but anyone expecting a full-blown Roland Emmerich misadventure will wind up severely confused. Baumbach handles the grand scope well without losing focus on the story or the themes of consumer culture comforts, America’s fascistic leanings, or the specific trivialities and chaos of family life. Yet, a lot is still missing that makes the book such a potent and bewildering absurdist statement. I walked away from the movie with a clearer idea of what makes the book so great and what’s missing from the film. Yes, this movie is still very entertaining and bewildering enough to work. Adam Driver and Greta Gerwig fit the roles well. Don Cheadle is wonderful as Murray Jay Siskind. The aesthetic is brimming with inventiveness and color. The grocery scenes look like they let Damien Chazelle shoot a candy store. I will probably watch it again when it hits Netflix and bask in its exquisite tones and production. This is a big movie which has the potential to be lost on the public at large and misinterpreted through reactionary tweets (he’s a professor in the studies of WHAT!?) but that’s what it’s like to live in a streaming world, where the toxic discourse hits your screen before the movie does. The first act of the film is about watching the teetering at the edge of the cliff and the second is the push, an energetic journey into Hell. Baumbach handles the transition into the more personal third with aplomb but doesn’t stick the landing. Avoiding Jack’s insecurities as a larger part of the film’s story was a mistake. The third act is severely weakened and the film ends in an awkward way. It’s alright though, two out of three still makes for an entertaining companion piece to a great novel.

RATING: 7 out of 10